Battery electric vehicles are designed to be a greener choice. However, while the absence of tailpipe emissions might make it feel like a no-brainer when you consider the energy it costs to charge and produce the batteries, are they really a cleaner option than the traditional internal combustion engine (ICE)?

At PE Strategic Consulting, we take nothing at face value. In this article, we’ll dig into the differences between the ICE and BEV in each stage to settle the tank vs. battery debate once and for all.

The Production Process

Most skeptics challenging BEVs tend to point to the battery production process first. This is a logical place to start since the production of the battery is easily the dirtiest part of the battery process.

Producing high-grade automotive lithium-ion batteries still emits significant amounts of carbon and requires the extraction of precious natural resources. Currently, an automotive lithium-ion battery costs more carbon to produce than it does to develop an internal combustion engine. However, a large portion of that pollution is created specifically by China, which has opportunities to significantly improve its footprint.

Chinese EV battery manufacturers emit 60% more CO2 to produce a BEV battery versus an ICE. However, if China were to adopt American or European manufacturing techniques, its carbon emissions would be reduced by up to 66%, making the battery production process cleaner than that of the ICE. Improvements in infrastructure, greener energy sourcing, and more efficient manufacturing techniques can all drastically drive greenhouse gases down, making BEV an increasingly greener choice.

Pump Vs. Plug

Whether you own a traditional ICE vehicle or a BEV, you’ll still need to refuel them with either gas or electricity—and neither is free of carbon emissions. So, which is better?

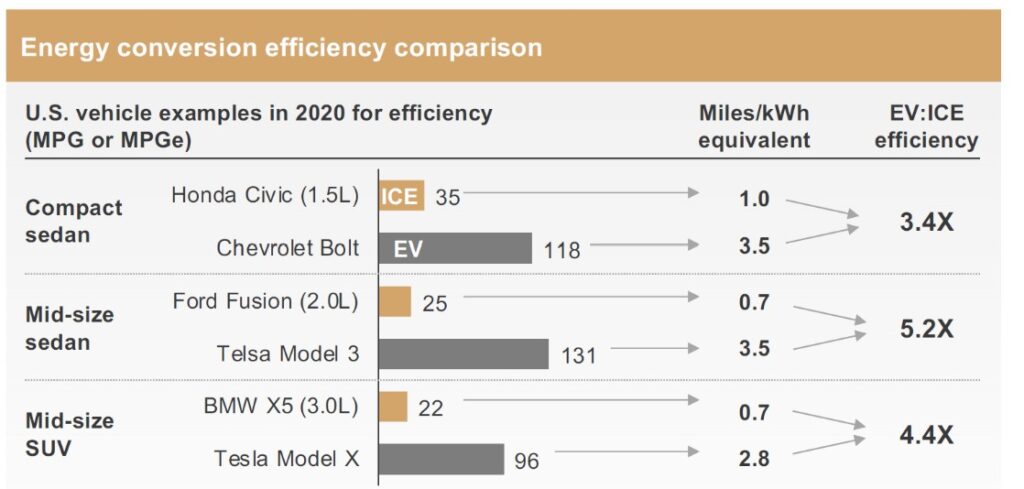

To start, we’ll examine the efficiency of each vehicle type—how long can the vehicle run on a single charge or tank fill-up? The EPA equates one gallon of gasoline to 33.705 kWh of energy, allowing us to compare ICE and BEV efficiency standards using a miles-per-gallon equivalent (MPGe).

As you can see in the chart below, when using MPGe, electric vehicles are 3 to 5 times more efficient than their ICE equivalents. The Chevy Bolt can achieve 3.4 times more miles on a single charge than the Honda Civic can achieve on a tank of gas. The difference only grows in larger vehicles. The Tesla Model X, a mid-sized SUV, achieves 4.4 times the efficiency of the BMW X5, and the Tesla Model 3 mid-sized sedan averages 5.2 more MPGe than the comparable Ford Fusion.

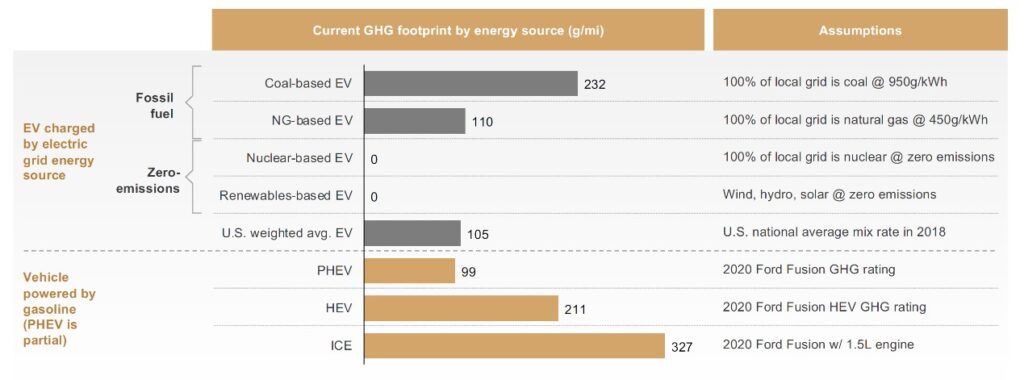

The energy differences don’t stop there, though. The BEV easily wins with more miles to the charge, but when we look at where that energy comes from (and the carbon produced to generate it), the BEV comes out on top again.

Even if the electrical grid your BEV charged from were 100% carbon-based, you would still have a significantly lower carbon footprint than that of a mid-size Sedan with an internal combustion engine. However, finding a local grid that still relies solely on coal would be hard to find.

In the United States, the use of coal has already significantly dropped and is expected to see an additional 7.7% decrease in the generation mix over the next four years. Instead, most energy companies are turning to natural gas, a much cleaner energy source, to power their grid. In 2018, natural gas accounted for 35% of the U.S. energy mix. Renewable energies are also seeing a rise, with hydro, wind, and solar accounting for 16% of the total energy generation and growing at a rate of 9% per year. With a shift toward cleaner energy generation, the BEV, which already has a much smaller carbon footprint, will only continue to improve its efficiency rating.

Download the full “Tank Vs. Battery Emission Comparison” report by Paul Eichenberg Strategic Consulting to learn more about BEV efficiencies compared to the ICE.

The Battery Afterlife

Finally, the battery lifespan and what happens to it afterward are important factors to look at when assessing its eco-friendliness. Currently, the recycling of lithium-ion batteries is limited. However, as BEVs grow in popularity, so does the focus on finding ways to reuse and recycle them. One of the ways some governments and companies are considering reusing the batteries is in the electrical grid.

After an EV battery runs through its typical 17-year lifespan—a lifecycle on par with ICE vehicles—most batteries will still obtain a significant enough percentage of capacity that could make them useful for storing energy in the grid. This “second life” could add up to 10 more years to the battery lifespan, significantly reducing its lifetime carbon footprint.

Recycling key components of the battery will also help further reduce its environmental impact. Material sourcing accounts for roughly 50 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions during the battery production process. Finding ways to recycle these materials, such as aluminum, nickel, and cobalt, would reduce the need to extract more of these natural resources, making the production process cleaner over time.

Winning in a BEV world

No matter how you slice it, BEVs are the vehicle of the future. Conventional ICE vehicles will continue to be phased out of the market, and with it, the parts and components that power it. If you haven’t yet developed a long-term strategic plan on how you will survive and thrive in a new, electric world, we can help. Contact us today to learn more about our strategic consulting services.